One of the major fault lines in libertarian theory runs between those who regard the state as inherently evil (the “anarcho-capitalists”) and those who contend that the minimal state, i.e. one limited essentially to the provision of national defense and domestic law enforcement, is morally legitimate. The anarcho-capitalist indictment of the state is quite simple and straight-forward: any coercion employed against innocent persons (those not themselves engaged in aggression against others) is wrong (the “non-aggression principle”). Since the minimal state, among other things, collects taxes on a non-consensual basis to fund its activities, it is morally objectionable.

The anarchist argument will not trouble those who start with different moral presuppositions. Thus, utilitarians would simply reply that the practical advantages of the state in terms of promoting the general welfare justify coercion, at least for its “core” functions. However, since Nozick himself embraces the non-aggression principle, this avenue is unavailable to him. Rather, he tries to show in ASU that because the market for protective services is a sort of natural monopoly, the minimal state could evolve (and presumably operate) in a manner that does not violate the rights of any party, thereby blunting the anarchist claim that states are intrinsically evil. Nozick’s effort is almost universally (and correctly I believe) regarded as a failure, so I will not discuss it further here.

Thus, we are faced with the question of whether the minimal state can be justified from Nozick’s natural rights perspective. I believe that the most promising approach to this challenge is to argue that coercion employed to fund the activities of the minimal state stands on a different moral footing than it otherwise would. This process starts with the observation that for Nozick our moral agency is the source of special normative status (see the discussion under the link “Natural Rights Libertarianism”). Accordingly, it may be possible to distinguish, from an ethical perspective, state functions that are essential for the preservation of moral agency and those that are not. Arguably, protection from foreign attack or criminal violence is a basic precondition to the exercise of our moral discretion, and thus justified by the very value that gives rise to side constraints against aggression.

So, we can pose this question by means of the imaginary case of a peace-loving island community threatened with imminent invasion by a bloodthirsty horde of barbarians who will murder many of them and enslave the rest. The islanders can successfully repel this invasion if everyone does his or her fair share through the contribution of goods and/or services. Accordingly, the islanders form a government whose sole function is to manage the defense of the island. To do so it requests donations with which to pay its new volunteer army and to make weapons.

Sadly, while most members of the community willingly give their fair share, there are hold-outs who either sincerely object to the use of force even in self-defense or who, on a calculating basis, seek to free ride on the contributions of others. Without the application of coercion against these holdouts, the defense effort will probably fail. In such circumstances is coercion by the island’s government justified? I believe it is, even against the sincere pacifists.

The basis for this conclusion rests on something like the “principle of fairness” first articulated by H.L.A. Hart. Basically, it is simply unfair for some members of a community to reap the benefits of the efforts of others while refusing to contribute themselves, i.e. by free riding.

Although more controversial, I believe this principle even applies to the pacifists on the island who do not regard expenditures on self-defense as a benefit to them. They must enjoy life or they would have ended it; and they must enjoy their property, or they would have given it away. Thus, they benefit from the defense by others of their lives and property. Pacifists may be sincere free riders, but free riders nonetheless. Therefore, the community, acting through the state, is entitled to force them to live up to their obligations.

Interestingly, Nozick considers and then rejects the principle of fairness by proposing a counterexample. However, his case involves a trivial benefit (entertainment) provided by members of a neighborhood group, and he correctly concludes that the holdout in his case is under no obligation to contribute to the supply of this good (see ASU, 90-5). He does not analyze examples of the sort constructed above, and thus fails to refute the principle of fairness, at least when it is restricted to goods essential for the exercise of moral agency.

Accordingly, I believe the principle of fairness remains viable as a justification for state coercion in the supply of national defense, at least when the state in question is a reasonably just one faced by a realistic threat of aggression.

You could always flee the island instead of treating other people as if they were your property, to be used to serve your own purposes. Non-aggressing individuals don’t have any enforceable obligations to society except those that they freely consent to. The “principle of fairness” is one of the principal reasons that the power and scope of the state has grown by leaps and bounds over the past few decades.

Steve,

I agree that everyone on the island has the moral right to leave, but this idea is fully consistent with the principle of fairness. This principle claims to govern what can justly be done to those who choose NOT to leave and still don’t want to contribute to the defense effort. I claim that our moral intuitions sanction coercion when the situation of the islanders in sufficiently dire (as described in my example). Thanks for the comment.

Mark,

I’m not talking about the pacifists leaving. I mean that YOU can choose to leave if you can’t defend yourself against the invaders. You can talk about the “fairness principle” until you’re blue in the face, but other people are not your property, to do with as you wish. The pacifists haven’t initiated force against you. You have no claim on them. You should deal with them on the basis of mutual consent. Period. That’s being a libertarian.

Another query: I was doing a routine Amazon search of other writings by Mark Friedman, and Amazon came up with some forthcoming books, one I believe was on “Assisted Suicide.” Is this a different Mark Friedman, or is it you? – Mike M.

Yes, a different Mark Friedman. Sadly, I don’t have a trademark on my name.

Pingback: Schools of Thought in Classical Liberalism, Part 5: Natural rights | Western Free Press

While the use of your “principle of fairness” seems to be just the problem of free-loading in general, I think a bigger problem you face is in the initial stage of your thought experiment.

You state that, “The islanders form a government whose sole function…” In an aim to defend the minimal state, you grant a priori that which claims to provide the basis of coercion against individual autonomy: the legitimacy of the state.

If they do indeed form a government, you and Nozick are no longer in the same page and you are not addressing his concerns. From your example, the state has formed out of consent, not through the invisible hand evolution of Nozick, at which point it seems unnecessary to even invoke your principle of fairness as a reason to force these pacifists to contribute.

Hi Jake:

Thanks for the comment, but I don’t think you really understand my argument. In response to your first comment, note that my version of the principle of fairness only applies to those public goods that are essential to the exercise of rational agency. So it differs from H.L.A. Hart’s version, which would justify coercion for any public good, e.g. basic scientific research, public arts, etc.

Second, Nozick’s “invisible hand” justification of the minimal state is based on consent. People voluntarily join private protective agencies, that over time consolidate into one big, happy protective agency. Do you really suppose that he, a hardcore libertarian, would attempt to “justify” a state built on coercion? It’s just that his invisible hand explanation fails, as virtually everyone who has examined it agrees. I am suggesting an alternative approach which acknowledges, and justifies, the existence of coercion against free riders for the purpose of military defense and law enforcement only.

Hi Mark:

Thanks for the reply. It seems that we are talking past each other. I’m hoping this post will elucidate my points and help you respond more accurately.

First, the onus is on you to provide a systemic defense of why the principle of fairness would only apply to goods that are “essential to the exercise of rational agency.” Where and how do you draw a principled line from Hart’s view?

Second, I never denied that the invisible hand approach of Nozick involved consent. Yet, the functions of consent in your hypothetical and Nozick’s derivation differ greatly.

In your example of the pacifists in the island, the creation of the state is via a Lockean social contract model, which is explicitly something Nozick wants to avoid. His derivation of the minimal state is an attempt to argue against the anarchist that the minimal state would inevitably and naturally form as a result of rational individuals’ actions (see: Gaus, http://www.gaus.biz/Nozick.pdf). That is also why Nozick goes to such lengths to come up with his principle of compensation — to justify how the state can legitimately compensate individuals for its prevention of their exercise of natural rights.

Thus, your attempt to defend Nozick’s justification of state coercion in matters of security is based on an entirely different foundation from Nozick’s.

In the OP I say, “Nozick’s effort is almost universally (and correctly I believe) regarded as a failure, so I will not discuss it further here.” So, of course, my view is entirely different from his. How did you miss this?

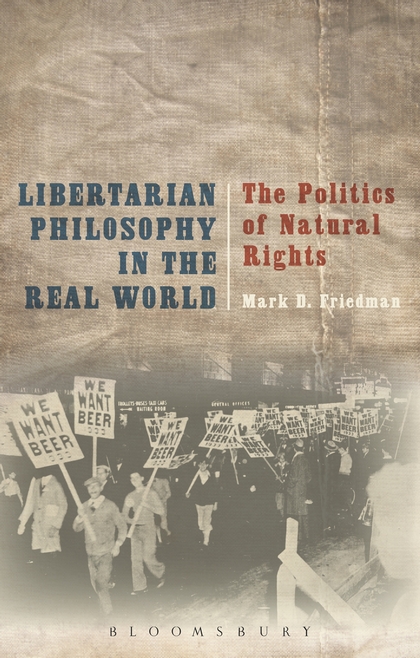

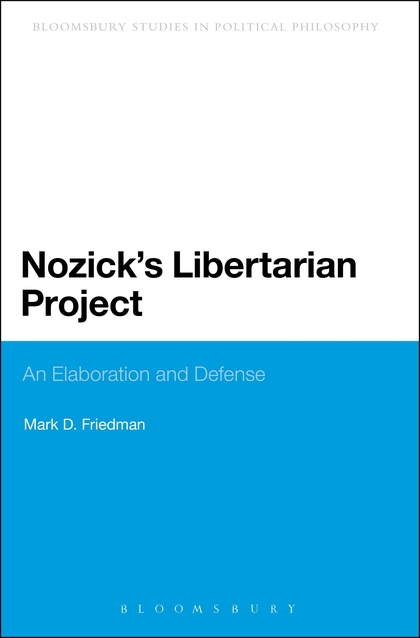

Second, I do not rely on social contract theory, because there are hold-outs. My argument is a justification for using coercion against these free riders. The short argument for this is presented in the OP; the much longer and detailed version, in Chapter 4 of my book.

From the OP: Accordingly, it may be possible to distinguish, from an ethical perspective, state functions that are essential for the preservation of moral agency and those that are not. Arguably, protection from foreign attack or criminal violence is a basic precondition to the exercise of our moral discretion, and thus justified by the very value that gives rise to side constraints against aggression.

Thanks for the reply Mark.

Sorry about missing your statement about intentionally not discussing Nozick’s account of the minimal state. (As an aside, “How did you miss this?” was not well-received — unnecessary adhominem, no?) I did not realize how lofty your goals were — to provide a different account of how minimal states would arise under a natural rights framework.

I am skeptical as to how successfully you’re able to tie your principle of fairness with a natural rights perspective. With a simple hypothetical, some derivative of Hart’s principle, and some claim on the importance of moral agency, you’re trying to provide a moral foundation for natural rights that not even Nozick or Locke provided.

Assuming the moral foundation as natural, however, I now see the appeal of your attempt to base some state functions on a different moral foothold.

Still, I wonder how defensible your claim, that some state functions are distinguishable on the basis that they are essential to the preservation of moral agency, is. Even if you disregard Nozick’s invisible hand account of the minimal state, I find it difficult to believe that you would disregard his account of the entitlement theory. Claiming certain functions of the state to be on a moral foothold would involve some kind of pattern in its distributive functions and it seems you would have to defend why this particular pattern would be acceptable over Nozick’s rejection of any kind of pattern.

Let me know what you think.

Very briefly: All I am trying to do here is supply a libertarian-friendly rationale for making would-be free riders on national defense pay their fair share. If they do so, they will permit other citizens to pay only their fair share, and not more. I don’t see any redistributive aspect, nor do I see any inconsistency with Nozick’s entitlement theory, which I enthusiastically endorse. I am afraid this is all the time I have to devote to this thread.

PS: The tone of your first two comments was not well-received on this end.

This will be my final comment as well.

Firstly, it’s regretful that my first two comments were considered to have an unwelcome tone. It certainly was not my intention.

Second, by redistributive, it simply refers to the collection of income from individuals by the state for the state functions. Whether it be for the purposes of fairplay or any reason your principle of fairness would draw from, your justification seems to be a patterned principle (in this case based on fairness). If you so enthusiastically endorse Nozick’s entitlement theory, it will serve you well to explain why this particular patterned principle is acceptable, since Nozick argues for a historical, non-patterned approach in his principle of justice.

I enjoyed this brief exchange. Best luck to you in your future endeavors and congratulations on the forthcoming publication of your book.

In re-reading this thread, it does now appear to me that I was overly harsh, abrupt, and combative, for which I now belatedly apologize. I must have been having a bad day.

Hi Mark,

I stumbled across your blog and I really like this argument that you’ve put forward. I do have one concern/question that I’m hoping that you can answer for me. In your article, you argue that coercion can be justified if it provides the environment that allows moral agency to exist. Having food or adequate medicine to live, some would argue, is a precondition for moral agency to exist. Does this argument for a minimal state open up the door for nationalized medicine and other forms of socialism? Thanks so much for reading this and I look forward to reading more of your work.

Hi Jacob:

Thanks for finding my blog, the complement, and your thoughtful question. To answer it, I must start by noting that Nozick’s argument for natural rights, which I essentially accept and discuss here, generates a powerful presumption against the coercion of innocent persons. Accordingly, while Nozick would, as a last resort, countenance coercive taxation to keep blameless persons from starving or dying from easily treatable diseases, he would certainly insist that the compulsion employed be the absolute minimum required to achieve the desired result. So, rather than forcing the entire country into socialized medicine, he would favor either cash transfers or health insurance vouchers to help the relatively small number of those truly unable to fend for themselves. I hope this helps. Let me know if you have any follow-up questions.

Hi Mark,

Thank you for the reply! I have a follow up question. Wouldn’t the situation of the food/medicine and national defense be different in that in the case of national defense, both the individuals who free ride and the individuals who have to coerce the free riders have their moral agency upheld or rights protected but in the case of the food/medicine social net only one side has it’s moral agency upheld and the other side’s is reduced? So in the case of the social safety net (food and medicine in this case) there wouldn’t be a libertarian fairness occurring due to the lack of equal effect on rights. Anyway I’m curious what you think and appreciate what you do for the cause of liberty.

Thank you again,

Jacob

Another good question, but the answer gets a little more complicated. Nozick would support a social safety net, despite the coercion it entails, under two rationales: (i) to avoid “catastrophic moral horror” (because rights aren’t the only thing in the moral universe) and (ii) his adaptation of Locke’s justification of private property. The latter requires a bit of explanation, which I undertake here: https://naturalrightslibertarian.com/2017/08/nozicks-adaptation-of-lockes-proviso/#more-1640. So, while it would be coercive to tax people to save blameless persons in dire need, it would not violate libertarian principles because such a commitment is required to morally justify property rights in the first place. Let me know if this is still unclear.

EDIT: Perhaps I should add by way of clarification that you are correct that the reasoning that justifies taxation for national defense (“essential public goods”) is different than that which warrants taxation, as a last resort, to support the blameless in dire need.

“Interestingly, Nozick considers and then rejects the principle of fairness by proposing a counterexample. However, his case involves a trivial benefit (entertainment) provided by members of a neighborhood group, and he correctly concludes that the holdout in his case is under no obligation to contribute to the supply of this good (see ASU, 90-5). He does not analyze examples of the sort constructed above, and thus fails to refute the principle of fairness, at least when it is restricted to goods essential for the exercise of moral agency.”

I’m confused as to how this distinction – between trivial benefits and benefits which are necessary for the exercise of moral agency – is relevant from a fairness perspective. Whether an agent unfairly benefits from a system is determined not by the nature or magnitude of the benefits produced by the system, but by the agent’s relation to the system (i.e. are they benefiting from the system, are they paying into the system, etc.). In other words, the unfairness here consists in the free-riding. But this free-riding is present even when the benefit is trivial. Thus, it is equally unfair if a person benefits from coerced entertainment without paying into it, regardless of how serious or trivial these benefits are.

I do think there’s a morally relevant difference between trivial benefits and more serious benefits. But it seems to me that the morally relevant difference has nothing to do with fairness. I think the fact that the benefits are serious is sufficient to justify coercing others to subsidize those benefits, independently of anything to do with fairness. After all, if it turned out that certain individuals would be better off without the minimal state (e.g. say they would have been able to fund their own private defense force), I still think it would be justified to coerce those individuals to subsidize a minimal state in order to provide serious benefits for others (assuming such coercion was necessary to provide these benefits). The seriousness of the benefits is what’s doing the work here, not the fairness.

Hi Jay:

Thanks for noticing my blog, and for your thoughtful comment. I’m not sure how much of our disagreement is semantic and how much substantive, but I guess we will find out. Although I label my theory the “libertarian theory of fairness” (because it proceeds from a similarly named theory proposed by H.L.A. Hart), it is based on underlying principles of justice. So, I continue to hold that the distinguishing feature of the coercion required to supply national defense and for Nozick’s public entertainment scenario relates to the nature of the benefit provided, and not simply the “serious” versus “trivial” degree. [edit]

To see this, it is necessary to take a step back and inquire why Nozick (and I) place such a high disvalue on coercion, which Nozick cashes out in terms of his famous “side-constraints.” The answer is that it is incompatible with our autonomy or rational agency, which he describes as including, in addition to the three classic traits often proposed (rationality, free will and moral agency), “the ability to regulate and guide [our] life in accordance with some overall conception [we] choose to accept” (ASU, p.49). Both cases clearly involve coercion that (appears to) violate Nozickian side-constraints, but in Nozick’s own example the only compensation is a trivial utilitarian benefit.

However, in the case of national defense the nature of the benefit provided is protection of the very human capability (rational agency) that gives rise to side-constraints. Thus, in my Nozick’s Libertarian Project I distinguish coercive taxation to support the public goods of basic scientific research and national defense in these terms:

Eric Mack, in his essay ““Nozickian Arguments for the More-Than-Minimal State,” puts the same idea this way: “The special character of the injury involved in rights violation suggests a constraint on what sort of compensation is due for rights-infringing action. If the injury is in the currency of a boundary crossing, the compensation must consist in the prevention of boundary crossing.” Accordingly, in Nozick’s case the good provided does not enhance rational agency, although it might increase the agent’s net pleasure, while national defense does.

It is not a question of making persons pay their “fair share,” but what they are being made to pay for. It is not just a difference in magnitude, but also one of kind.

I hope this clarifies things at least a little.